PAST TRUTHS: THE INDIGENOUS PRESENCE

Our Blue Mountains bushland property splits into three levels as it gently tumbles from a ridge and descends into a valley. I have never taken this place where I live for granted.

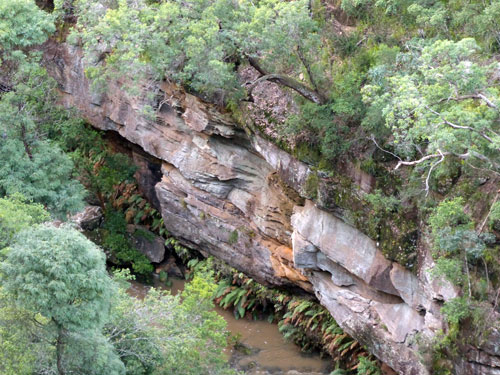

Beyond our back border, the bushland soon comes to a large rock shelf, under which stretches an impressive cave. From there you can see the valley floor, covered in trees and smaller, native bushes which hide a creek from view.

The valley’s opposite side ascends more steeply.

In this valley there are many places where Aboriginal people left evidence that they once belonged here. The cultural and religious significance of these places also helped give them their identity, especially through the many associated stories they knew. Just as I identify with this area where I have lived for the last four decades, so must the indigenous people who were here for countless generations before my family. I can rattle off many stories from memory that are associated with my time in this place. Early intruders into this country often, for various reasons, failed to appreciate that the Aboriginal people they encountered would also have stories of this place, stories that were important to them and their ancestors. I can only acknowledge the indigenous presence and respect the strong, special bond they had with this land. What it must have felt like to have such places taken from them, sometimes with violence, is very difficult to imagine.

Over the years, while working in my backyard, I have dug up stone pieces that possibly could have been Aboriginal tools. I sometimes look across the valley and know, from my reading, that there are scattered rock shelters over there that house ancient artwork. Solitary walks along the fire trail to the the area known to us as The Bluff can occasion thoughtful contemplation. Many times I have found myself thinking about those who, long before me, looked and also marvelled at the view in front of them. I find myself sometimes wondering what it must have been like before Europeans began intruding into this country.

Over the years, while working in my backyard, I have dug up stone pieces that possibly could have been Aboriginal tools. I sometimes look across the valley and know, from my reading, that there are scattered rock shelters over there that house ancient artwork. Solitary walks along the fire trail to the the area known to us as The Bluff can occasion thoughtful contemplation. Many times I have found myself thinking about those who, long before me, looked and also marvelled at the view in front of them. I find myself sometimes wondering what it must have been like before Europeans began intruding into this country.

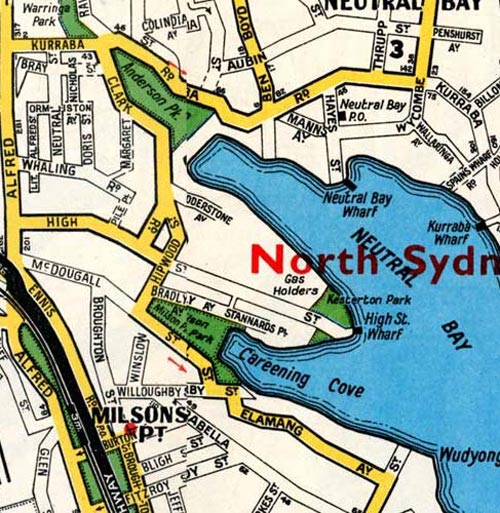

When I was a child growing up in North Sydney, it never would have entered my head to think that where I lived and played, Aboriginal people had once done the same. The shell middens I saw on the small, sandy beaches around Sydney Harbour had no meaning for me. The appropriation of indigenous languages for nearby place names, like Kirribilli, Kurraba and Cammeray, was never considered or commented upon. Any cultural or religious significance these names carried would definitely not have been up for discussion.

Any reference to Aboriginal people implied that they lived somewhere else, far from where I lived, perhaps in the centre of Australia. It was not that they had left here, but rather that they had never been here.

The literature and films that I was exposed to as a child helped to reinforce this belief. The New South Wales School Magazine included a series of cartoon-style drawings by Miss Joyce Abbott, ‘illustrating various aspects of the life and customs of the Australian Aborigines’. The black and white drawings were of naked Aboriginal people performing a variety of activities. I read about how a bone could be pointed at someone and they died by ‘sorcerer’s magic’. I learnt how the medicine man ‘has to pretend to remove the magic’ to save the victim of bone pointing.

One of the books I had to read in my early years at high school was We of the Never Never. A novel by Jeannie Gunn, it was based on her early married life on a remote, Australian cattle property. The copies which we were given to read had been used by many classes over preceding years. They sometimes contained supposedly witty comments from previous holders of the copies. I still remember one written on a copy of We of the Never Never. On the title page was scrawled an alternate title suggestion, ‘Black Man’s Piss’. For this joke to work, the implication seems to be that the Never Never, far away from ‘who knows where’,was where you would find Aboriginal people.

The only film that I can remember seeing at primary school concerned those Aboriginal people living in the deserts of Central Australia. They seemed closer in my mind to the ‘natives’ in the Tarzan films I saw at my local picture theatre or the ones that peopled The Phantom comic strip in the Sunday papers. They had no relevance to, or connection with, a residential suburb like the one in which I lived as a child.

Over the years, my return visits to North Sydney have allowed me to see the area in a new way, as a place where there has always been an Aboriginal presence. In so doing, I believe my understanding of the history of the area and my childhood days there take on new meaning.

Early in 1868, Prince Alfred, the Duke of Edinburgh, visited Sydney. Before his departure, preparations had been made to treat him to a performance of a large corroboree by Aboriginal groups. They came from ‘several distant parts of the country’, including Burrangong, Araluen, the Clarence River district and Moruya. (Sydney Morning Herald, 12 March 1868) There probably had not been such a significant number of indigenous people in Sydney since the early years of the European arrival. The corroboree was scheduled to take place at Clontarf, on the northern shores of Sydney Harbour.

Livingstone Mann witnessed a rehearsal for this planned, special corroboree and wrote about it. He remembered that the Aboriginal people ‘were collected from the different districts’. This leaves in question whether they all came of their own free will. He recalled them ‘practising for this great event, making their boomerangs from the local trees and using them, as they danced round with their bodies painted in many designs. The grotesqueness and facial contortions were such that one could never forget.’ (Mann, p196)

And Mann did not forget. He was over 70 when he wrote about the corroboree which he had witnessed when he was only seven years old.

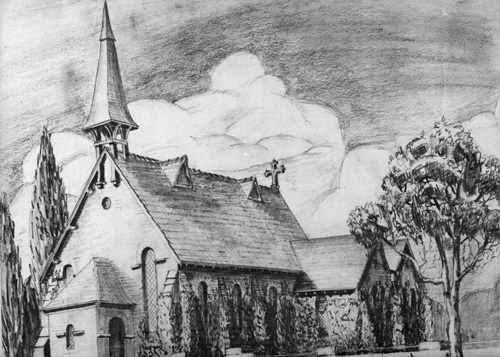

The Aboriginal people whom Mann had seen, camped and prepared for the dance on the site where St John the Baptist Church now stands at Milsons Point, just opposite the stairway to the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

Assuming that the selection for this ‘royal performance’ was based on ability, it is sad that we do not know any of the names of the accomplished Aboriginal performers who were chosen to take part. Corroborees are normally performed at night. If that was so with the rehearsal which Mann had seen, then the sight and sound must have been quite special when viewed across the water in Sydney.

St John the Baptist Church

Apparently today St John the Baptist Church is referred to as ‘the church by the bridge’. Designed by the well-known church architect Edmund Blackett, it was built in 1884, just sixteen years after the corroboree referred to by Mann. The vestry and sanctuary were added in 1900. The church hall was not built until 1909. The hall was used for Sunday School classes which were still operating in the 1950s when I was in attendance. My brother and I had been baptised at St John’s as babies and regularly attended Sunday School there, winning book awards for our good attendance record. I also sang for awhile in the church choir.

The significance of an Aboriginal ceremonial dance being practised on a site later to accommodate a building consecrated for religious purposes, should not be overlooked.

Unfortunately the Prince never saw the large corroboree planned in his honour. An attempted assassination prior to its performance, saw the cancellation of all the remaining, celebratory events.

Since learning about the corroboree, the church site, as a special place of memory, is further enriched for me by this new knowledge.

I also regret that I did not know about the indigenous presence in those wild spaces we played in above Kurraba Road and Anderson Park. I still remember, with some trepidation, another group of boys we once met there. They decided we had trespassed into ‘their territory’ and started throwing large stones down on us. We hurriedly retreated to safer parts.

According to Mann, in this same area, Aboriginal people ‘would come in from far and near each year and camp for some time in order to receive the annual distribution of blankets and rations on the Queen’s birthday’.(Mann, p196) The period that Mann was remembering was from the 1860s and 1870s.

The terrible injustice exposed by this information is very saddening to think about, especially when we know that the place to which they were returning was theirs to start with and had been taken from them. Before 1788 the same land and sea areas provided the Aboriginal people with their necessary food requirements. Now this was no longer the case. The disappearance of the fish and fauna they depended on had far reaching effects. Besides the food that these animals provided, the skins for warmth and comfort (eg the rugs and cloaks we see used by Aboriginal people in early European drawings and paintings) and the bones needed for the tools to make things were gone. With this threat to self sufficiency went the accompanying knowledge and skills.

The terrible injustice exposed by this information is very saddening to think about, especially when we know that the place to which they were returning was theirs to start with and had been taken from them. Before 1788 the same land and sea areas provided the Aboriginal people with their necessary food requirements. Now this was no longer the case. The disappearance of the fish and fauna they depended on had far reaching effects. Besides the food that these animals provided, the skins for warmth and comfort (eg the rugs and cloaks we see used by Aboriginal people in early European drawings and paintings) and the bones needed for the tools to make things were gone. With this threat to self sufficiency went the accompanying knowledge and skills.

And what relevance would this queen, whose birthday was being celebrated, have had to the indigenous people anyway? My childhood memory, relating to this same place, concerning trespassing and violent reactions, now seems somewhat of an irony.

Mann lamented the disappearance of indigenous sites around Neutral Bay.

[left:Neutral Bay 2018]]

‘There was a large over-hanging cave full of markings of large hands done by the black fellows. Upon investigation the other day I find the cave has been completely cut away during the process of reclamation.’(Mann, p200)

I imagine this happened during the construction of the sea wall to reclaim the tidal flats and establish Anderson Park.

Mann also mentioned the destruction of another significant carving.

‘Just above the post office, Ben Boyd Road, there was a fine specimen of aboriginal carving, an emu on a flat rock. A pity this was not preserved! A cottage now occupies the site.’ (Mann, p200)

Erasing evidence of prior occupation, whatever reasons are given, has significant ramifications for the following generations. Hindsight very rarely brings insightful solutions. In this case the wrongs have already been done and cannot be revoked. I realise how beneficial it would have been, as a child, to have some of the knowledge I now possess regarding the indigenous presence in, rather than absence from, the area where I grew up.

As if on cue, Conrad Martens painted View of Sydney from Neutral Bay, providing us with a visual representation of the landscape as Mann would have seen it. Painted around 1857, that is roughly a decade before his coming to live there. In the foreground is the elevated, rocky ridge, where the Aboriginal people camped and waited for their rations. It was still this wild space in the 1950s when I encountered the stone-throwing gang.

View of Sydney from Neutral Bay c.1857 Conrad Martens

The Kirribilli and High Street headlands that form Careening Cove are centred in the lower half of the painting. The former headland protrudes furthest into the harbour, as if trying to reach a yacht in full sail. Tall masted sailing ships can be seen in the harbour. In the background lies Sydney, with its modest spread of buildings, including Government House. The main feature of this painting is the dominant spread of bushland across the landscape, along with a smattering of wildflowers, just as Mann described it in his article.

Trying to understand the past has never been an easy pursuit. Choices presented themselves and decisions, rightly or wrongly, were made. We live with the outcomes. I believe that the study of history has been and continues to be extremely beneficial when honestly attempting to face the outcomes.

© Jim Low

before the Warringah Expressway

Reference:

Mann, L. F.: ‘Early Neutral Bay.’ Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Australian Historical Society, Vol xvii Pt iv 1932, pp183-208.