A RETURN TRIP TO A HIDDEN HAWKESBURY MEMORIAL

Just over an hour’s drive from where I live is a special place that I always value visiting. It is the site of a small monument, in the form of an obelisk, that was erected in 1952. The obelisk was deliberately erected in the vicinity of the former Sackville Aboriginal Reserve and Mission.

Situated on the banks of the Hawkesbury River at Cumberland Reach, it stands under the protective, outstretched branches of a massive fig tree. This tree seems to literally grow out of a large, isolated lump of stone. The obelisk reminds those who happen to find it that Aboriginal people have a presence there.

The return visit was made on a perfect, sunny winter’s day. As we drove slowly up the narrow track to the memorial site, we were stopped by a sturdy metal, locked gate. No signage had warned us of this gate and to make matters more difficult, there was no adequate turning space on the track.

A locked gate implies a boundary which clearly says, ‘No trespassing’. But this is a public space. I wondered whether I would have entered if I had never been here before. Without a sign to explain the reason for the gate, it felt unwelcoming and disappointed me. It was not a great start when about to revisit a place that has become important to me. Ignoring the gate and walking to the memorial, I wondered whether it was erected for protection or secrecy.

Back in early 1953 a Sackville resident, Mr Roy Mitchell, offered to surrender a lease of 40 acres. It had originally been part of the Aboriginal reserve. The Windsor and Richmond Gazette, 25 February 1953, reported on Mitchell’s generous offer and his assertion ‘that since the erection of the memorial to the aborigines on the reserve last year, a good deal of public interest had been taken in the area, and it had been visited by a number of cruisers and visiting parties of tourists, whereas before the memorial was erected a stranger was very rarely seen there.’ He believed that the land which he offered would be a practical addition to the reserve, providing space for ‘a beautiful scenic walk there, on the shady side of the mountain’. Mitchell’s enthusiasm to inform and share the area and its history is in sharp contrast to the unwelcoming feel I experienced on my return visit.

There was no evidence of any recent maintenance around the memorial site. The new plants which I recalled from a previous visit were gone. Branches had fallen across pathways and also near the memorial. Despite the sun, on entering the grassy area where the obelisk stands, everything became darker and the colours lost any vibrancy under the giant umbrella shade of the large fig tree.

The memorial’s aesthetic beauty seems to lie in its natural colouring. I was reminded of the subtle tones of a gumtree’s trunk. Pinks, browns, blues, yellows and greens blend together in a unique mix of colour, allowing the memorial to slip unobtrusively into the environment. As I stepped away from it, just like a little gecko can magically blend with its background, so too did this memorial obelisk on the Hawkesbury bank.

Mr P.W.Gledhill, the man whose idea it was to erect the memorial, chose an obelisk for the task of remembering the Aboriginal presence in the Hawkesbury region. After the First World War, the obelisk became the most popular form of monument. As K.S.Inglis wrote in Sacred Places: ‘For every cross in the landscape, Australians raised at least ten obelisks.’ (p153) And the reasons for this, he concluded, were the following:

‘(An obelisk) was easily and if need be cheaply supplied, non-sectarian, traditionally recognisable as symbol of death or glory.’ (p153)

Perhaps Gledhill could also have believed, as Inglis did, that:

’Obelisks could bear a variety of meanings and none at all.’(p35)

The 1818 obelisk in Macquarie Place, Sydney, for example, is just a starting point to show from where ‘all the public roads leading to the interior of the Colony’ were measured. An obelisk was also chosen at Kurnell to mark the landing place of Captain James Cook in 1770. Its height towers over the three metre obelisk at Cumberland Reach.

A couple of months prior to the unveiling of the Cumberland Reach obelisk, an advertisement appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald. It advertised coach tours that left from Martin Place in the City and went to Kurnell. The advertisement begins as follows:

‘Every Australian and every visitor should see Captain Cook’s Landing Place, Australia’s most historic spot. You will proudly remember having stood where Captain Cook stepped ashore and walked where first white man trod. See Hallowed places marked by well Inscribed obelisk and the very spring from which the Endeavour water tanks were replenished.’

It can be rather unsettling to ponder how a country goes about measuring the historic value of a place and its sacred or ‘hallowed’ qualities. In the country’s collective memory, I have no doubt that the obelisk at Cumberland Reach has not been given a fighting chance to achieve the questionable claims made for Kurnell in the above advertisement.

While on a field trip in the area researching for her The Real Secret River: Dyarubbinproject, historian Grace Karskens met Roy Mitchell’s son, Dennis. Still residing in the district and present when the memorial was unveiled, he informed her that the obelisk was originally painted white with black and gold lettering.

Close inspection of black and white photographs taken in 1952 on page 13 in Roy Brook’s Shut Out From The World, appear to support this. I made a point of looking for any evidence of paint on my recent visit but there was none. When, why and how it was removed is a mystery. Perhaps it was originally painted white to make it more visible to passing river travellers. Why anyone should want to paint sandstone, especially when they had taken the time and expense to have a stone mason redress and inscribe the obelisk, as Gledhill reportedly had done, remains another mystery. (Windsor and Richmond Gazette, 18 June 1952)

There is another hidden memorial which can be found, with some difficulty, upstream at Windsor. This memorial is also on the Hawkesbury’s western bank.

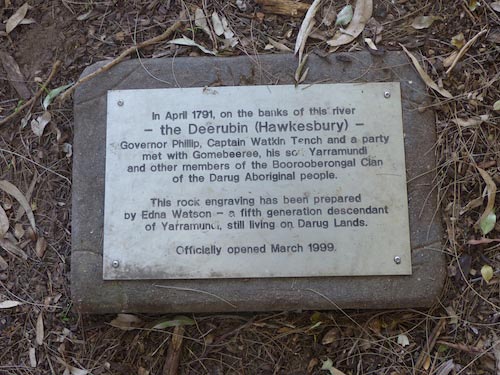

Two opposing pairs of feet, one bare and one shod, have been engraved on a small rock outcrop. This simple representation reminds us when ‘Captain Phillip, Watkin Tench and a party met with Gomebeeree, his son Yarramundi and other members of the Boorooberongal Clan of the Darug Aboriginal people’ in April 1791. The accompanying plaque from which the previous quote comes, also informs us that the engravings were prepared by Edna Watson, ‘a fifth generation descendant of Yarramundi, still living on Darug lands’. The memorial was opened in March 1999.

With no signage or pathway to it, the memorial is hidden in a cluster of trees. Several times in the past few years I have attempted to find it and failed. A few weeks ago I had better fortune, literally stumbling on it. I thought of the life-sized statue of Macquarie, not far from here on the other side of the river. I again contemplated the process we use to rank the historical importance of something.

On my visits to Cumberland Reach, I have never had any reason to question the integrity of Gledhill and his philanthropic motives for erecting the memorial. I do not see it as a memorial that either marks closure or death for theAboriginal people of the Hawkesbury. I see it as facilitating memory as well as engaging the desire to know and understand. Like the simple memorial at Windsor, these beacons of memory help to keep alive stories whose narratives reveal to us both good and bad things that have happened around these places.

|

|

I believe that the memorial at Cumberland Reach aims to draw people to this picturesque setting where perhaps in quiet reverence they can be inspired to discover and understand more about our shared history. These are the gifts I have gratefully taken away from there on my visits to this special place.

© Jim Low

References:

- Jack Brook, Shut Out From The World, Deerubbin Press, 1999

- K.I.Inglis, Sacred Places, Melbourne University Press 1999

- G.Karskens, Life and Death on Dyarubbin, Griffith Review 63)